My new Brownie camera came with Dad’s advice. “Always label your photos so you’ll remember the people.”

“Don’t be silly,” I said, “I’ll remember.” Dad was right, of course. Sometimes I stare at an old photo and struggle for a name.

My mother followed my father’s wisdom and labeled everything. When she died at age ninety-two, her scrapbooks came to me. Each January, I dismantle a few. I don’t keep photos of sheep, flowers, or koalas—sorry, Mom. If I can unglue a few people photos, I’m happy.

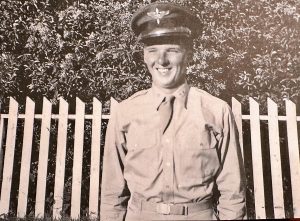

The last scrapbook I tackled was from the 1940’s—white ink on black pages. I released paper thin envelopes and photos from tiny silver corners. However, nothing from this album gets tossed. I’m not decluttering anymore. I’m on a mission to connect—connect—connect. I’m returning photos and letters to families of the airmen from Dad’s pilot training days: John (Johnny) Whitaker, Freddie Sawyer, and Rosebud.

John Whitaker was easy to trace, as he was a member of the 100th bomb group, my father’s group. John was something of a “renaissance man” according to his nephew—a jock, a decent artist, a musician. And then a pilot.

Whitaker was killed in action on August 17, 1943 when as co-pilot of the B-17, Picklepuss, his plane was shot down by German fighters. According to reports, enemy fire caused the bomber’s wheels to lower, unknown to the crew. Gear down was a signal for surrender. German fighters approached to escort the B-17 to landing, but were fired upon by Picklepuss. Fighting intensified. The bomber fell. Six airmen were killed, four became POWS.

I returned a letter from Whitaker’s mother, Marie, written in 1944. Marie talks about her three sons, all who served in the war. Even though her son John was killed in action, Marie gives hope to my mom that her love would soon be released from the POW camp.

Mom kept many photos of Freddie Sawyer, an English pilot who trained with the class of 43-B at Moody Field, Georgia. Freddie’s letter of January 19, 1942, mentions how hard the training hours, how good the American food. His passion is clear: finish training and get onto active duty. Freddy believed that 1943 would be a good year for the Allied nations. It wasn’t for him, he died on a mission. Photos of Freddie and his letters to Mom, were sent to his nephew in Australia.

The nickname, Rosebud, remains a mystery, but not the person. Rosebud was John J. Stocker, Jr. (J J), later assigned to the 341st bomb group. All photos marked Rosebud were taken in August of 1942 when my mother visited her boyfriend Billy, (Dad) in Bennettsville, South Carolina during training days.

Stocker, an only child, resided in Watertown, NY at the time he joined the military. I called an office supply company in Watertown with the same name and got an old phone number for another J J Stocker, Rosebud’s son.

Stocker’s son told me he was two months old when his father died. His mother had mailed photos of him as a new baby, but the package was returned unopened. Rosebud died on January 24, 1944, flying over the hump—the eastern end of the Himalayas. J J had never seen photos of his father in uniform and was deeply moved that I would give them to him.

“It looks like your father and mine were true friends. I am forever indebted to you. Seeing my father’s photos brought an enormous smile to my face.”

Mom’s scrapbooks and albums are almost empty. My heart is full. Because my mother labeled her scrapbooks, I continue my never ending mission to find more families of those airmen who trained, served and suffered with my father during WWII. But even if I never find another family, placing photos of a vibrant young man, nicknamed Rosebud, into the hands of his only child, who never knew his father, was an enormous gift.